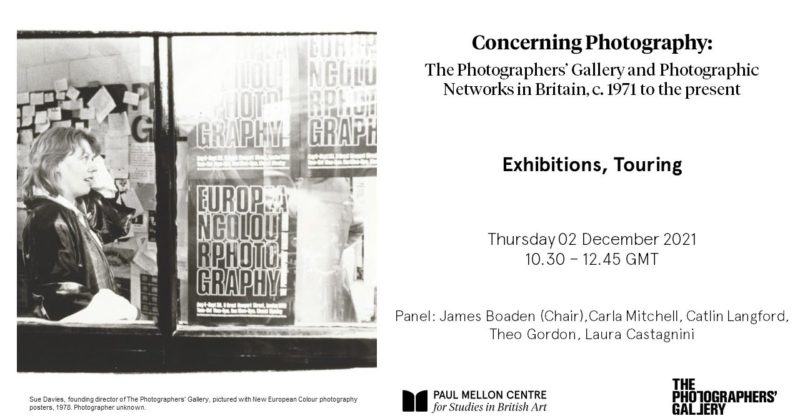

Concerning Photography, Day 3: Exhibitions, Touring (Morning session)

– Welcome, everyone. Thank you so much for being here and joining us today. I'm head of exhibitions at The Photographers' Gallery. My name's Clare Grafik. Thank you for joining us for our final day of this illuminating conference. I hope you've been able to follow the other days where we've heard fascinating research on a huge range of topics from "Ten.8" magazine, materiality, and the establishment of galleries and organisations focused on the photographic image. We're thrilled to be here for what promises to be an exciting and interesting day of debates and discussions ending with a presentation by artist, Antonio Roberts. Before we move to James Boaden, who will see more on the panellists and the themes for this morning session on key touring exhibitions and the circulation of the image in other formats such as the festival, and its process and its panellists, I just wanted to say a few words regarding the collaboration and how we came to the ideas that will be explored today.

Our discussion started in 2017 between Mark Hallett at the Paul Mellon Centre, and Brett Rogers at The Photographers' Gallery, and began with a study day as well in 2017, not long after their first discussion. We're really excited it has grown into this wonderful programme where we can celebrate new scholarship and perspectives and the study of photography. I'm particularly excited about this morning's panel, which looks at the presentation and display of photography from the 1970s to the 1990s. Before we move to our speakers, here are a few words on housekeeping for today. The session contains four 15-minute papers with a Q&A session after the second and fourth papers. After the first Q&A session, there is a short 15-minute comfort break. Audience members can type questions using the Q&A function. This session is being recorded and made available to the public and closed captioning is available.

Click the CC button on the bottom right-hand of your screen to enable captions. Lastly, a few thank yous to finish off. To Sarah Turner, Shawna Blanchfield, Daniel Kovi, and the rest of the team at the Paul Mellon Centre who've been absolutely amazing to work with. My colleagues at The Photographers' Gallery who put this together and this morning's speakers and the audience. And now to art historian, James Boaden. Thanks very much. – Thanks, Clare. So a very warm welcome to everybody joining us. It's great to see so many people here again today. And I've really enjoyed watching the past few days of this conference. So as Clare said, this morning, we're going to be talking about exhibitions and touring in particular. And we're going to have two papers in this first session, and then another two later on. So I'm going to introduce the first two speakers. They'll give their talks back to back, and then we'll have a little bit of time for Q&A after that. So do please add your questions to the Q&A function below, do engage with the chat as we're going along.

Now, the first paper is written by Ruby Rees-Sheridan, who unfortunately can't be with us today. But her paper will be delivered by her colleague, Carla Mitchell. So Ruby Rees-Sheridan is the curatorial and archive coordinator at Four Corners where she co-curates exhibitions exploring hidden histories of photography and works on the Four Corners archive. And she's currently the project coordinator on Four Corners' hidden histories project, where she's carrying out research into the history of Half Moon photography workshops, laminated touring exhibitions, which is the subject of the paper today which will be delivered, as I mentioned by, Carla Mitchell, who is artistic development director at Four Corners. So has assured me that she'll be able to answer questions on the paper even though she didn't write it herself, if that makes sense. Following that will be a paper from Catlin Langford, who is the inaugural curatorial fellow in photography supported by the Bern Schwartz Family Foundation at the Victoria and Albert Museum. At the V&A, she's working on the autochrome collection, which will inform an upcoming publication with Thames and Hudson V&A.

Before that, she was assistant curator at the Royal Collections Trust where she specialised in 19th century photography. So I think we'll start with Ruby's paper presented by Carla. So Carla, I can ask you to share your screen, then we can begin. – [Clare] If you want to turn on your mic and camera, please, Carla. – Can you see and hear me now? – [Clare] That's great. Thank you. – Apologies for that. Okay. So good morning, everybody. And it's really great to be here. So this is really research in progress that Ruby Rees-Sheridan has been doing into the Half Moon Photography Workshop's early exhibitions, and particularly the audiences who attended some of these exhibitions. So I'm gonna start with a little bit of background and explanation about the early history of Half Moon Photography Workshop. So Half Moon Photography Workshop, for those of you who may not know that name is much better known by the name of Camera Work after its renowned magazine. It played a central role in the development of socially engaged photography in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s. Parts of a vibrant and transformative moment that has been described by many in this conference already.

So today, I'm going to argue that the Half Moon Photography Workshop's innovative forms of exhibition, which were often shown in non-traditional spaces, help transform the cultural status of photography for audiences of the time. So why is Four Corners Archive… Just a little bit of explanation. The archive of Half Moon Photography Workshop and "Camera Work" Magazine form part of Four Corners Archive. Four Corners was a closely related film workshop and neighbour in East London. And when Camera Work closed in 2000, Four corners reopened its gallery and dark rooms to create a centre for both film and photography. So we've been developing an online archive of our early work for the past five years and very much seeking to develop the archive as a site for socially engaged practise study and collaboration.

And the… Along with the "Camera Work" magazine, less well known, but equally important worthy, Half Moon Photography Workshop touring exhibitions, and here's some images of some of them. These were very much part of the central aim of the organisation to democratise the practise of photography and to engage with new forms of social documentary and representation. So the Half Moon Photography Workshop has gone through several iterations and names. It started life as the Tiny Half Moon Gallery in Aile Street, Whitechapel, East London, where it was in the face of the foyer of the half Moon Theatre, a radical French theatre. And audiences could view photography on their way in to see a bit of wrecked place in the space convivial, but rather cramped setting.

Here, you can see on the outside, there are some posters being put up for Nick Hedge's factory photographs. You may just be able to see that. So in 1975, Half Moon Gallery really changed significantly by putting on a series of seminars, which discussed contemporary British photography. And this engaged photographers, educators, curators, including the Arts Council's newly appointed photography officer, Barry Lane, to engage in critical debates around British photography. And as well as being a very important moment, attendees included Joe Spence and Terry Dennards of Photography Workshop, who had dedicated to an idea of a transformative community photography.

And together with Half Moon Gallery, they formed Half Moon Photography Workshop later that year. So the new group develop their ideas, in particular, through "Camera Work" magazine, their publishing project. And other early members included Paul Trevor, Mike Goldwater, Tom Pickton, Shirley Read, and Ed Barber among very, very many others. There… And this is it's quite well known, but it's worth repeating that their statement of aims, which appeared on the back of the first issue of "Camera Work" stated that the running of Half Moon Photography Workshop will reflect our central concern in photography, which is not, is it art, but who is it for? So it rapidly… The group rapidly established itself as a forum for critical debates on the politics of documentary, representation, the role of the photographer, and the use of the medium in oppositional politics.

And complimenting the magazine, there were the touring exhibitions laminated and sent all around the UK and nationwide, internationally. So lamination was a technical innovation for the time. The unofficial origin story is that it was thought up to prevent photographers work getting damaged from the leaky roof at the Half Moon Gallery. In any case, it was the early member, Ed Barber, who developed these lightweight, but durable exhibition panels into touring shows. And you can see a box with one of them in this image here. Over 50 of these laminated exhibitions were produced between 1976 and '84, and sent around the country by British Red Star Parcel service. And they showcased an emerging generation of British photographers, Daniel Meadows, and Nick Hedges, to name just a couple.

But many, many more documenting working lives and disappearing traditions and shedding light on international conflict and injustices closer to home. At the time, there were just a handful of spaces dedicated to photography in the UK. These exhibitions brought new forms of imagery to nation… To audiences nationwide from art centres and universities to prisons, churches, bookshops, and even a laundromat. Their adaptable format enabling thousands of people to view photography for the first time.

But how was this work received by audiences? So this paper takes the exhibition comments books as a starting point to examine what audience responses might have been at the time. There is very little documentation of the exhibitions in situ. We have many booking forms. Well, very little else. But what we do have are these extraordinary comments books which provide a rare and fascinating record of visitor encounters with the exhibitions. So here you can see, inked in black, "Comments book: Please use it." And the comments book function, not only is a place to write nice platitudes, but as a critical and discussive space. Flicking through, it's evident that these exhibitions attracted a wide range of visitors and sparked strong opinions. The pages sometimes read like a heated Facebook thread as university lecturers, students, local councillors, youth leaders, museum attendants, and self-identified innocent bystanders dispute the impact and politics of the photographs on display. From the academic to the obscene, the thoughtful to the reactionary, these contributions provide a valuable counterpart to the ideas expressed in "Camera Work" magazine.

They provided an unmediated, democratic space in which a plurality of voices and cacophony of opinions jostle together, and where long before social media people socialised, organised, and exchanged ideas. So here's just a few examples of exhibitions and some of the comments that they elicited. So the exhibition, "The Thirties and Today", was researched by Terry Dennett, designed by Ed Barber, and first shown at the Half Moon Gallery in the summer of 1977. Against the backdrop of the Grunwick dispute and strike actions against wage reductions, it drew parallels between the experiences of unemployment and poverty in the 1930s and the 1970s. And you can see here, an ironic juxtaposition between two images, the unemployed workers on their way to the Ritz before Christmas, 1938, in protest. And below, a photograph by Ray Rising of a trade union leader at an indulgent working-together luncheon. Suggesting that by the 1970s, trade unionist leaders had sold out to capitalism.

So Terry Dennett, who put together that exhibition along with Joe Spence look to the 1930s and explicitly anti-capitalist work of the British workers film and photography movement as a source of inspiration in the aim to use photography as a socially transformative tool. And this is another exhibition in that vein. So visitors to this exhibition were certainly aware of the historical parallels. You can see a couple of comments here.

So A. Gardener writes, "The reason why the photographs are so significant is because the position of the proletariat hasn't changed since the 1930s. But many, equally, wanted to see more contemporary photographs." So on the other page, there is a comment at the bottom which says, "Photos and commentary excellently juxtaposed and very informative. But if the title is 'The Thirties or Today', why not more photos of today? There are numerous comparisons that one could make, e.g.

The rise of Oswald Mosley, Cable Street, to NF Movement in North London this April. or Jarrow crusade to Right To Work march. If placed side by side, the immediate similarities would become glaring." So I also should point out that some, as in the top comment, were more interested in the beer and the pub next door. It's unclear why Dennett had to focus so specifically on archive photography in that exhibition, but it is certainly the case that he was critical of contemporary photographers. Here's an article by Spence and Dennett in "Camera Work" seven, "The Unpolitical Photograph", where they challenged the motion among photographers that their work was somehow neutral or apolitical. In fact, they argued that photographers must consider how photographs are used and decoded by various audiences.

And I would argue that the comments book certainly provide an insight into how audiences did decode the photographs. So here we have some responses to the exhibition survival programmes by Exit Photography Group. You can see a couple of comments at the top. Kim Longenoto, documentary filmmaker comments, "Some of these photographs literally made me gasp in amazement, delight, anger." Others are more blunt. Comment at the bottom says, "One rule for the rich. One for the poor." So the 1977 exhibition, Growing Old, taken by Mike Abrahams originally for the book, "The Alienated: Growing Old Today", written by 75-year-old activist, Gladys Elder, focused on hardships suffered by older people in the 1970s. And Abrahams, Mike Abrahams, the photographer worked closely with older people's groups to produce this exhibition, living on the equivalent of a weekly pension, which, as the press release noted, was the amount being granted by the Arts Council of Great Britain.

This popular exhibition was shown widely, including in Holloway Prison. And many saw his collaborative and accessible approach as an innovative way to convey important messages. There was a sense that the exhibition was a valuable, educational resource that should be seen by wider audiences. A visitor from Grench Pensioners proposed that the project be exhibited at social security offices as well as all pensioners' meeting places.

Similar requests are prevalent throughout the comments books, suggesting that viewers felt the exhibitions had the power to inform public opinion and change policy making. A very different exhibition here. In 1982, "Story of a Home Birth" by Karen Michelson presented a feminist critique of medicalized births in hospitals and touched on issues of choice and control in women's experiences. And here you can see a number of comments. And what is striking about them, and most of all, mostly they're anonymous as the sense of relief and gratitude expressed by visitors. No instructions are given to us in this society. It is good to see blood and skin and cloth. I do still feel confused about having a child. But I do feel quite sure now of the way I'd like to give birth. So a final example is the 1983 exhibition, "The Police, the Community, and Colin Roach", which resonates strongly with contemporary issues. This documented the demonstrations resulting from the probable murder of Colin Roach, a 21-year-old black man who died in Stoke Newington Police Station in London.

And the case produced huge protests against police brutality and harassment. Here, visitors commented on the importance of seeing images of police repression at a time when these were largely absent from the mainstream press. Others felt that the images should be taken out of the gallery to open up their reception to non-traditional audiences and function much more as a campaigning tool. More work needs to be done to find out where this exhibition toured. So in conclusion, the Half Moon Photography Workshop's touring exhibitions evidently offered a rare opportunity for audiences to engage in critical conversations about photographic images and representations in the 1970s and 1980s Britain. And arguably helped change the cultural status of photography as a whole. The comments books represented the democratic space for audience comments and engagement filled with chaotic, unmoderated, and sometimes heated dialogues. Today's audience evaluation forms mediated by the demands of data collection and funded targets cannot hope to capture such vivid responses. So how might we create spaces today in which such dialogues could take place? Perhaps a starting point is to revisit the Half Moon Photography Workshop's central concern.

Not, is it art, but who is it for? Thank you. – [James] Thanks so much, Carla. So we'll move straight on into the next paper, which is Catlin Langford's paper on Signal, the Signals Festival, which I'm really looking forward to. And then we'll come together at the end for some questions. So do start adding your questions to the Q&A tab either on the paper that Carla's just given, Ruby's paper, and also as we're going through Catlin's.

So welcome, Catlin. – Thanks, James. I just want to firstly thank the Paul Mellon Centre and the Photographers' Gallery for the opportunity to speak and for organising such a fabulous conference. So to begin, a review in "The Independent" published August, 1994, proclaimed, if the idea of a festival devoted to women photographers fills you with dread, all strident, feminist ideology, and questionable exclusivity, the nationwide event, Signals, coming your way soon promises to be a pleasant surprise. The article refers to the 1994, Festival of Women Photographers. Signals seems almost idealistic today, consisting of around 400 events across the United Kingdom and Europe. It was committed to exhibiting and making space for women photographers and artists, and sought to be inclusive and community-minded. Moving away from being London-centric and embracing regional diversity and arts. Yet Signals is largely forgotten today, or only a footnote in the histories. While the festival strove to alter landscape of photography and make permanent space for women in museum collections, close to 30 years since the festival's conclusion, there is still a significant disparity in the representation of women photographers in museum collections.

In this talk, I'll explore the conditions which inspire Signals and discuss the aims and activities of the festival and its legacy. I want to preface this talk by saying most of the Signals archive is missing or destroyed. What remains is largely housed in Val Williams Archive at the Martin Parr Foundation. Furthermore, there are little visual accounts. As I've been told that at the time, people didn't really create visual records of exhibitions, which is slightly ironic given the vast number of people involved were photographers. Therefore my research, which remains ongoing, is based on catalogues, articles, or advertisements, and primarily through the oral accounts of those involved. I'm still working to gain a full sense of the festival. So this presentation is based on my work so far. So what were the conditions leading up to Signals? Inspired by second wave feminism, there's a movement from the 1970s to reassess the place of women artists, both in historical accounts, as well as contemporary society, and address their absence.

Val Williams landmark in 1986 publication and related exhibition, "The Other Observers", is rightfully considered pioneering. It looked at women's multi-facet involvement in photography and studio practise, propaganda, photo-journalism, and vernacular photography like snapshots. It came after Ann Tucker's work and other publications followed including "Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers" by Jene Moutoussamy-Ashe and Naomi Rosenblum's "A history of women photographers". These publications were notable as there was a clear difference in women's representation in the photographic press. In the 1980s, creative camera only showed women, 22% of time, in their portfolio pages. While in the "British Journal of Photography", only 10% of the portfolios were by women. And this very much reflects the photography exhibitions of the period, both in Britain and abroad. In the 1970s and '80s, as many have commented on, you see this real reconsideration of the significance of photography, particularly around the 150-year anniversary of the widely accepted birth of photography in 1839. The Royal Academy's 1989 exhibition, "The Art of Photography" was an unofficial survey of the photographic medium that featured a near-full women after the 92 photographers shown.

In the same year, the V&A's Photography Now faired slightly better with seven women featuring in a show of 28. Considering an international example, in the US, the National Gallery of Art's, "On the Art of Fixing a Shadow", featured 220 photographers, but only 20 were women. "Valium" stated in 1989, such tokenism seem not only unforgivable, but also provide a proof that the status of women within the medium was not in any way secure. What is surprising that these exhibitions followed not only some of those publications, but also the 1988 Spectrum Festival dedicated to women's photography consisting of over 40 exhibitions across London. One of the headline exhibitions was Helen Levitt at the Photographers' Gallery.

And at the present Levitt Exhibition at the Photographers' Gallery, there are articles discussing the festival. And every woman article notes Spectrum could not be continued as to quote, The Arts Council turned them down flat, and they are operating a small grant from Greater London Art. photography itself is little valued as an art form in Britain. And promoting women's photography is not exactly high on the art's establishment agenda. While one-off, Spectrum showed that giving place…

A space to women's photography was needed and worthwhile. It was followed by the 1989 Serpentine Gallery staging of Susan Butler's exhibition, "Shifting Focus", credited with bringing the work of many significant women artists to the UK for the very first time. These exhibitions, the bad and good, were the impetus to put together a festival of women photographers that move beyond London, encompassing all of the UK. While Williams also noted that she thought there would be more activity, exhibitions, research, and events following the other observers, this perceived lack made her seek other ways to show and promote women's work. Signals thus came into being in February, 1992. The direction of the festival was informed by a steering committee that was established organically through people's contacts, leading to the formation of a group of 14 curators, academics, artists, photographers, and writers, and I've shown them here. The festival aimed to bring about greater awareness of women's practise and encourage a culture of showing, exhibiting, and collecting photographs by women. At the time, women didn't have the same access to patrons or relationships of major museums as enjoyed by their male contemporaries.

Michael Ann Mullens of the Hackney Flashers noted to quote, at the time women, didn't get exhibitions, didn't get commissions. They still had to battle to have representation and women's work was not pushed forward. Signals aimed to put things right, make women be seen, be shown, and provide a platform. Val Williams wrote in "The Guardian", "Women have only recently moved from the fringes of art and photography to its core. It is vital that they should remain there." The committee met monthly at the Photographers' Gallery, and everyone was engaged initially on a voluntary basis. This relates to the festivals funding, or lack of. As many involved, as the festival attests, the Arts Council did not provide sufficient financial support. Some have argued this reflects the lack of recognition of the festival and its significance as well as the low status of photography in an unofficial hierarchy of the arts.

Only in March, 1994 was funding granted, albeit very little for the scale of the festival, 60,000 pounds. This enabled the hiring of three paid staff, including Monika Baker as festival coordinator and director, and the ability to maintain an office at Interchange Studios on Dalby Street. To galvanise support and establish a programme, the following flyer was sent to arts and cultural organisations, and members of the committee also visited organisations across the UK. This was part of the aim to include and give agency to regional organisations. Grace Robertson stated to quote, Signals was conceived as a festival which would be formed from regional initiatives, not as one controlled by London-based group with a curatorial agenda. There was an overwhelmingly positive response and the committee received numerous proposals. The festivals and national platform, giving those working in cultural organisations a reason and confidence to suggest events on women artists and photographers. Being part of a wider movement also made it easier to gain the support of boards.

At this time, as Liz Wells noted, regional councils controlled their own arts funding. So therefore could direct money towards the festival, which was important given Signals' lack of funding. In terms of Signals own board, there was no vetting process. Anyone who applied was featured in the programme. To help facilitate the festival, regional coordinators were involved including Ann McNeil in the Southeast and Bernadine Everiso in London. Signals officially ran from September to October, 1994. Some of the events have their own start or end dates, but were included in the programme. For instance, in response to Signals from August to November, 1994, the Photographers' Gallery devoted its spaces entirely to women. The lack of funding and the small timeframe makes the sheer number of events and expanse of the festival all the more inspiring. Overall, there were 400 events included in the festival programme, which is shown here. While there was a desire to avoid being London-centric, there was also a desire to avoid being British-centric.

On this point, Europe was the theme of the festival, influenced by the Channel Tunnel opening in 1994, as well as increasing relations between the British and European photography scene. For instance, the exhibition "Warworks" shown here curated by Williams and featuring works by Hannah Collins and Anna Fox was initially shown at the National Institute of Photography in Rotterdam as part of the Signals programme and would later be exhibited at the V&A, their first all-female show. Central to its theme was the conference messages from Europe. Image, art, and media held at the National Museum of photography, Film, and Television. Among the speakers were Maud Sulter, Maggie Murray, Astrid Proll, and Mark Harworth Booth. It was thought that issues raised in the conference would inspire future Signals Festivals. In terms of exhibitions, the programming feature to quote, large-scale exhibitions by established names to modest, local shows by little known or amateur photographers.

Many notable institutions took part. An exhibition on Edwardian women photographers was shown at the MPG. And the significant "Who's Looking at the Family?" was shown at the Babkin and included in the programme. Outside of London, the Royal photographic Society staged an exhibition on Ingo Maurer and 50 Women: 50 Photographs featuring work by, among others, Julia Margaret Cameron. Mark and Birmingham present an exhibition dedicated to Madam Yevonde. The Manchester City Art Gallery held an exhibition of Cindy Sherman's works.

Northern Arts in Newcastle show Grace Robertson's "Mother's Day Off" series. And portfolio in Ederan exhibited most of the Sticker series. There was also desire to bring work by women to spaces that people frequented every day. This inspired Shirley Reed's retrospective of Joe Spence who had died the previous year at the Royal Festival Hall. Reed wanted to connect with audiences who were going about their daily business. And you see this in other initiatives, including Billbroads, an exhibition using public advertising sites in Bristol. And Moving Stories, an exhibition on the Merseyside underground in Liverpool. A review, which appeared in "Art Monthly" wrote… The director of Fest is not shown here. Exhibitions also took place in shop windows, libraries, churches, sports centres, and schools. In addition, there were many community initiatives. Exhibitions were put together through open calls, youth education, and community groups. In Hereford, women from traveller communities were supplied with cameras and produced works over a two-year period leading up to the festival.

These were then exhibited at the Cathedral School Galleries. In Styal Prison in Cheshire, women prisons produced photographs reflecting their experience, which was then exhibited and disbursed as postcards. The festival included networking opportunities and workshops introducing and training women on photographic techniques. Workshops were not strictly limited to creative production, however. At Format, the first women's photographic agency in Britain, women could take part in a two-day course introducing them to work and picture libraries or as picture editors, thus supporting all aspects of women's involvement in photography. In terms of themes, digital photography and technologies featured strongly, and the Signals catalogue including an essay by Beryl Graham, which discusses the facility of digital technology to enable audience real-world participation and collaboration.

The artists, Liz Milner, who's shown in this article here, remembers attending workshops on how to use Photoshop. And these were run throughout the UK. There was also a real focus on projects that dealt with women's unique lived experiences like women's health, including "Our Bodies Ourselves" in Nottingham and Karen Eslie's "Techniques of The Body" at Viewpoint Gallery in Salford. Experience with motherhood were also commonly raised, including the young mothers photography project at North Shields People Centre and getting around to a pram at the Kelvin Young Women's Group at the Sheffield Town Hall. In terms of the festival's programming, there was an aim to be inclusive. Those involved with the board note, however, with hindsight, perhaps there could have been greater diversity. In terms of representation of artists and photographers of colour, this largely came from the inclusion of regional community groups and spaces. In Bradford, the community art centre showed so far, young, Asian women travelled to Seville based on work by women community groups. In Newcastle, the Todna Black Women's Photography Group exhibited at Benwell Library. And in Nottingham, EMC… EMACA Visual Arts held an exhibition highlighting black women and their achievements entitled, "Auspiciously Black and Female".

Monika Baker admits, however, more could have been done. And she states to quote, It simply wasn't on the agenda. There was a focus on gender and sexual identities but primarily exploring the lesbian experience. For instance, Average With Looks worked with the Liverpool community to consider lesbianism and homophobia. And their work was shown in Liverpool city centre, including projections on buildings. Maggie Murray who was on the board observed that transsexual identities were not explored. And in addition, there was little mention of gender fluidity despite this being one of the first occasions where Claude Cahun's work was exhibited in Britain.

It's hard to determine the reception and response to the festival except through reference to press articles at a time. For the most part, the response to the festival was positive. However, some articles discussed the event being separatous, overwhelming in scope, or amateur. In one particularly heinous article that the festival was described as to quote, Obnoxious and unworthy. Sadly dated, the silent aggrievance apply for a grant and Signals signs you up. Sherman's work was decreed as narcissistic charades and Joe Spencer's work written off as artistically insignificant. Illness is not a creative endowment. I refer to these terrible quotes to give a sense of the sexist and negative opinions that prevailed and were published at the time and reinforce the importance and requirement of Signals. I find the issue of these articles is they basically miss the point. The festival sought to give confidence to women to exhibit and fight for their works to have space. And by extension, those working behind the scenes to feel confident to exhibit works by women. As Bridget Ladenoir recalls, after the festival she'd quote, certainly felt confident doing books and projects on women photographers.

In many of the articles, Signals is positioned as a biennale and the answer to the lack of photography festivals in England. There was Aile in France and Spain had Primavera Photographica. There was a discussion about Signals 1996 with future Signals not needing to focus on women as there'll be parity between the representation of genders. Whilst flagged in the minutes, Signals 1996 did not happen nor really did parity between representation. Lack of easily obtainable funding. At that stage, there was already an overspend at the festival. And the extensive work involved is reason as the lack of Signals 1996, not a lack of desire. Though as Maggie Murray states, Signals 1994 did make a difference, even if very small. At the time, there was an awareness of the significance of Signals. And for this reason, the festival archive was donated to establish a women's museum where it was unfortunately lost. In the years following Signals, there was increased awareness on the need to show women's work, but there was still a sizeable gap between representation in both exhibitions and collections.

And this remains the case today. And this is something that's really being addressed on multiple levels. In 2015, Tate held a conference looking at women's photography organised by Fast Forward. Established by Anna Fox, Fast Forward works to make women photographers more visible. And similarly, Firecracker promotes women working in photography. Institutionally, roles have been established at the MPG and more recently, at the V&A to address the lack of women's work. As the V&A recorded, women make up only 15% of their photographs' collection. Exhibition programming across Britain is seemingly addressing the lack of representation. Consider the 2019 women photographers at the Lightbox in Woking, Four Corners exhibition on immigrant women photographers, and Photo Oxford's 2020/2021 programme dedicated to women.

While I felt Signals was pioneering, as Shirley restated to quote, it didn't feel pioneering. It was just necessary and overdue. And I think this is still the case today. And I would like to end, firstly, by thanking everyone who has contributed to my research. One of the points that kept coming up in our discussion was how women's history has become lost. And this was certainly the case for Signals. Therefore, I'd like to use this platform to say, if any of you have information relating to Signals, please do get in touch and I'll be very grateful. Thank you very much. – Thanks so much. Yeah. So if I can ask Carla to switch your camera back on, we've fairly rollocked through that and we're 10 minutes early, so we've got plenty of time for questions and conversation.

So I do really want to encourage everyone here to add their questions and comments to the Q&A tab. I thought that was a really fascinating pair of papers to look at together. Partly to do with the historical distances between the two moments. But also really kind of thinking about what the aims of touring something nationally on that kind of scale might be. I suppose, Carla, a question that I had was to do with, I was just reading Noni Stacey's great book where she really positions Half Moon within a kind of local community. I'm very much kind of thinking about it as somewhere with a sense of place and programming for the kind of immediate environs.

And I kind of wonder how far that stretched for the touring shows, you know. How those shows related to the places where they were being staged at that time. – Yeah, that's a very good question. And kind of quite a complex answer. So yes, absolutely. There was a particular focus on histories of local community in the East End of London, particularly among some of the earliest exhibitions. And in fact, those tended not to be the touring ones. But in terms of the touring ones, I think it's quite a mixed picture. But I certainly think of exhibitions such as Nick Hedge's factory photographs as a particularly good example where, you know, he very much enacted that idea of a community photographer of basically took photographs of people in factories in the Midlands.

Many of whom were from, you know, were newly arrived migrants from the Indian sub-continent in particular. And he not only sort of stayed and photographed them over long periods of time, but also interviewed them. So there are still oral histories that accompany those photographs. So I think that would be a sort of particular example. Judy Harrison, who did a whole project on small farms in Staffordshire equally is another one of sort of living and working with farming community, and particularly women, actually, often who had continued on the farm after husbands had died and things like that. So, yeah, there are some key examples of that. Although I'd say it's a mixture in, you know, for that very key strand. – Great. And Catlin, I was struck, I suppose, by the difference actually between the historical moments between the two papers. And the Carla's writing about… Or Carla's "Mouthpiecing of Paper" about a moment when feminism itself is a really kind of motivated project in a way that is quite different to that moment in the 1990s. And reading some of those kind of horrific and patronising headlines, it seems to me to be as much about a kind of backlash actually against feminism rather than thinking about women as practitioners, per se.

And I kind of wondered, you know, whether Signals was really positioning itself as a feminist festival in the way that it was being read by the press, or whether it was making a kind of distinction between women's work and feminism as a political project. – Yeah, so this is something I've spoken to quite a bit with the founding sort of steering committee. And some of them say that it wasn't about being feminists overtly. That didn't come up. That wasn't part of their politics. But others say, of course it had feminist aims.

And that was kind of the grassroots was, like, having that exposure for feminist work. But given that a lot of the programming and when it comes out, it's just sort of talks about it being a space for women to show their work. So then that backlash that comes out, I've read those really terrible quotes. But even a lot of the sort of headlines that you see where they're talking about women being snappy, and it's kind of quite negative and patronising. That sort of does seem to be a backlash just because it's women getting together.

And Val Williams actually wrote a response to that really terrible article that where she says, you know, 14 women coming together is quite intimidating. So even though they weren't directly positioning themselves as being feminist, I think the fact that they were doing these kinds of initiatives put people on edge a bit, and that's why you see this sort of backlash. And certainly now I think you would see as a feminist and giving space to women is a feminist thing. So I think it definitely that influenced that sort of quite terrible response, yeah. – Could I just add to that sort of from the "Camera Work" perspective? 'Cause I think it's really interesting.

Obviously, you know, "Camera Work" was quite, I think, a male-dominated institution in many ways. And I mean, it's interesting because feminism within the magazine really doesn't come through until the early 1980s, and that is a lot to do with the personalities within the magazine. So just one example, which I think is really interesting that, you know, that there was this pull, if you like, between a kind of humanist documentary representation, where the focus was really about the great image and a pull towards representation in which, you know, the image in a way was less important than what it was saying. There's just a particular example of, again, Nick Hedge's image of a woman factory worker, which I think is on the front of Issue 10. And that created a great battle within the collective as to whether that should be on the front cover because a lot of the men in the collective felt it wasn't the best image, but it was making a feminist statement.

And so the… You know, the women felt very differently. So there are those kinds of struggles going on. But I think feminism itself is not overt in the pages until much later. – Thanks, Carla. So there is a question in here, which to an extent, I think Catlin, you sort of have already answered at the end of your paper. But Michael Pritchard writes, were there future Signals and was there any legacy from the first festival? – Well, yeah, as I said, they did want to have future Signals. A lot of the early press, certainly. And maybe by the time it came around to the festival, it didn't have as much exposure, but it was about being a sort of rolling biennali and it would keep going. And Grace Robertson writes about, you know, the future Signals wouldn't just need to be devoted to women because it… There would be, you know, equal parody and men could come on board and it will all be wonderful, but this didn't happen.

And a lot of the reason why Signals 1996 didn't happen and future festivals was funding. But also I think the people were just completely exhausted. They were doing it on a voluntary basis in addition to their own work. And, you know, Val Williams alone was doing numerous exhibitions at a time. So it was quite a big take on. And I think just the lack of support from both, you know, funding boards.

But also, they talk about really struggling to get funding from, you know, private donors really influenced why there wasn't. And in terms of legacy, I sort of discussed that a little bit. It's really hard to measure these sorts of things. But just looking at, you know, numbers and collections, I think there's only been like a 5% shift in the number of women represented in collections, which is, you know, in 30 years isn't stunning, so, yeah – Yeah, I mean, just a quick shout out to one of our other speakers who spoke in the first session. I'd really recommend to anybody listening here, if they didn't hear it earlier in the year, the conference that Taous Dahmani put together, "Let Us Now Praise Famous Women", which I sat and watched at home late like this. And it was really incredible for thinking both about the kind of historical moment that we've been talking about as part of this conference, but then also really thinking about how we could shift ideas in the future and pick up on the legacies of some of this action from the past.

We've got a question from… Which I haven't read it yet, so I hope it's clean. From Annabella Pollen who writes, "Were some of the critique of Signals about amateur photography in part?" She says, "I recall interviewing someone as part of my history of amateur photography research who had taken part in Signals and she said it was dismissed due to being by women, but also by amateurs and thus seen by some as amateurish." – Yeah, so this is… They did include a lot of amateur groups as part of their programming. It was that idea that anyone could take part. But this is quite a unique criticism towards women's work that comes up a lot that, you know, it's amateur because it's, you know, produced by women or they were not skilled. And one of the things that, Carla, you mentioned about, you know, it wasn't a great image to put on the front cover.

This comes up a lot. They say, "It wasn't, you know, their best work." But that doesn't… Criticism doesn't always necessarily come up around male work, certainly at the time. So I think that criticism of it being amateur, sometimes it's positive. You see in some articles in Newcastle, there's these wonderful images of elderly women holding out photographs they've taken and saying… I think there's a quote like saying like, "I'm famous." Kind of thing, and it's positive. But then in the criticism where it's saying, you know, amateur, it's a real negative thing. And they're trying to sort of reestablish that link between women's work being amateur and therefore not of significance, so, yeah. – Do you think there was a conscious decision to… Because the program's really striking because it mixes both kind of commercial photography with artistic photography with someone like Cindy Sherman, someone like Madam Yevonde, who's somewhere kind of like in the middle of all sorts of things.

And then with amateur practise, do you think that there was a conscious decision when they were programming this may be to kind of fend off that sort of criticism? – I think very much speaking to everyone who's sort of been involved and who I've been able to speak to first, it was everyone could take part. And it was really just about exposing the sort of multifaceted nature of women's work, but also I think the multi-facet nature of photography. There was, you know, commercial studio practise. You mentioned Madam Yevonde, but they also showed, you know, Edwardian studio practise because like Alice Hughes who had sort of been overlooked a bit, but incredibly significant in her time.

But also looking at sort of photojournalism just… And sort of amateur photography clubs. It was really about showing that photography was multifaceted and women were involved in all of it. And so that is kind of, I think, the main part of it was just trying to show that women had a space in that history. But I think as well, it was also… By showing all of that, it was really just about exposing and giving women space as much as possible and giving people that confidence. So they might start off in like a small exhibition and be part of a camera club. But that doesn't mean that then don't evolve into something more or take out something with format or something like that. There was that real, just about really giving confidence. And that's something that I sort of mentioned, I think, is really missed in the articles.

They're not seeing it as a positive thing. They're sort of seeing that as a negative thing. – Yeah. – Carla, I don't know whether you might like to pick up on this question around the amateur, because I think it's quite a sort of tricky question around Full Moon as well. – Yeah. I mean, it's a really interesting one. I think it goes to the same place as what Caitlin's been discussing really. Because, you know, those… The look at sort of representation within photography, you know, was pulling away from, you know, these kinds of ideas of the great photographers tended to be people like, you know, Paul Strand or Bill Brandt, whoever. And, you know, very much more towards things like the vernacular, you know, Blackfriars Community Project with young people was a big initiative for only camera work, magazine articles, for example. So, yeah, they were very much, I'd say, probably two different tendencies going on, which were… Could often be pulling in different directions. And I think really, you know, it was very interesting hearing the presentation on "Ten.8" the other day because in a way I think that took over where "Camera Work" left off or kind of where "Camera Work" disintegrated slightly and possibly was the victim of these pulling in different directions.

You know, the sort of politics around representation and identity were then taken forward by "Ten.8" and possibly also embracing more of those ideas around the, you know, the incidental or the vernacular or the amateur being important. But I'm not an expert on that. So others might disagree with that. But yeah, I mean, and certainly in the subject matter, you know, of looking at issues again, early exhibitions, whether it was older people or, you know, date women's jobs, women giving birth, I mean, the Hackney Flashers was also an exhibition at the Half Moon Gallery. Things, yeah, I mean, they also did early exhibitions on around disability, which I think at the time was just perceived as sort of bizarre, you know.

People didn't understand why this should be a subject for an exhibition and much in the same way as Catlin has talked about maybe the Joe Spence material, you know, around health. So I think there were all these kinds of areas, which, yeah, which at the time… You know, now we probably see them as obvious, but at the time were, you know, were very challenging subject matters to take on. – Yeah, and this– – And just on that point…

Sorry, is that okay? Because Annabel has put in this idea about amateur being about, you know, showing family things and that as well. And just on that point about women's health, I think there's also that it's so important, and it's true. Like, these things around women's health and family moments weren't seen as art or even seen as worthwhile photography projects. But I think it's also missing that value of being sort of these experience reflected. And Carla, I really found that powerful where you wrote…

You spoke about that women saying she's now decided about how she wanted to give birth. Like, these things are so powerful to be seen and that's something that was also missing in a lot of the criticism of the event, yeah. – Yeah. I mean, I just find it really interesting to kind of think about actually what… How much a photography might mean during this period. And actually, this probably covers both papers. Because we think on the one hand about this category of the vernacular, where we're thinking about things like family snaps and what have you. But actually, there's a whole other kind of network of camera clubs, people who are working as amateur photographers in their spare time making work. My mom was an amateur photographer in the '80s when I was a kid. And I remember being dragged around to these sort of camera club shows and they were full of in a really…

Sort of as a seven year old, I just sort of giggled embarrassingly at these kind of nudie women and things. There's a whole kind of other culture that this is kind of working in dialogue with during this period of time, which I think, certainly to my knowledge, is much less well researched or talked about than things at the more kind of vernacular end. And which certainly wouldn't be interested in subjects like childbirth family photography was considered to be vernacular in a way that these sort of… I don't wanna call middlebrow. Middle, "Amateur Photography" is the name of the magazine. These sort of amateur photographers we would be working with. I don't know whether you'd agree with that or have thoughts on it. – Just, yeah, I think it's interesting. And I mean, the other thing, you know, Half Moon did a lot with these huge… Because they had to raise money all the time. They never had enough. They did these huge jumble sales, you know, where the sort of great and good photographers would donate work and they would have…

You know, they would have raffles and they would sell equipment. And if you see the images from these sales at the time, they're absolutely packed. There's obviously this huge appetite for photography at the time. But also just to comment maybe slightly differently, James, but I think it links to what you're saying is, you know, I think the other thing about the "Camera Work" initiative, which is important along with the kind of looking to the great humanist photographers is that they were also about an opening up and a democratisation of the use of photography by everybody. And, you know, there were many photographers who came through them who were absolutely not trained. And there was very much an embracing of, you know, that actually, if you took a good picture, you know, you took a… You had an interesting perspective, then, you know, you could have a show. You could… People used to come in through the door with a portfolio and someone would say, "Great, this is lovely.

Yeah, let's do an exhibition of your work." So there was also that, and that is something that hasn't really been looked at very much, the number of people who actually developed in that way. – And completely agree. I think that was the same point with Signals was that if you had something interesting to say, if you had something, you come on board. And I think, you know, Shirley Reed was with Half Moon and she was also with Signals.

I think the politics, therefore, there's that sort of lining up there. And the other thing I think that was kind of interesting just to note is this idea of amateur photography. The barbican who's looking at the family that was shown as part of Signals featured sort of a snapshot photograph of a young girl. It was one of these first moments when they started to put vernacular amateur photography in the galleries. And you see, that's quite a big thing now that's happening.

So it's kind of… But I think the value in that comes from it being historical amateur. And I think today, we still have these sorts of divides around what is valuable amateur and what's not. And it's something that I think could be looked at forever and it's really interesting. – I mean, I wanted to know perhaps a little bit about what you both saw as kind of historical models for these kinds of exhibitions. Because, Carla, I suppose I was struck by how, like… With particularly the use of the train to transport these exhibitions in these kind of pre-packaged boxes really reminded me of the sort of, you know, the revolutionary Keno train. And there seemed to be a really kind of, you know, sort of almost avant-garde-esque model of distribution, even though there's a level of the everyday going on in the content perhaps, and the commitment to a sort of factographic documentary.

And I kind of wondered, you know, what sort of historical models they were drawing on. And Cat, and the same sort of question, you know, where were they drawing, and we'll maybe come back to this actually with the papers in the second half. Where were these curators kind of drawing on these ideas from? – Shall I attempt to answer that? That's a very good question. And I'm not sure I know the answer entirely.

But I do wonder if it does go back to the point in the paper about, you know, that inspiration from the 1930s. The workers' film and photography clubs in the 1930s actually existed far more powerfully in places like Germany and Russia and possibly the US than they did in the UK. And in fact, I think there's a question as to how much, you know, Terry Dennett in particular maybe overemphasised their importance in Britain in the 1930s. But nonetheless, you know, that was, you know, I think the era they looked to in terms of initiatives around democratising and opening up the use of these media for political change, you know, as tools really. And so it's interesting that you picked up on the idea of, you know, the trains and so on, because there are many descriptions by early members of precisely this sort of, you know, this initiative which involved a van and you would drive the van down to wherever it was, Paddington. And they would literally be reloaded as this, you know, in the old days you would be able to do.

You would put them all in the parcel van and off they would go and they would be distributed. And at the end of the other end of the line, someone would collect them, open up the box, and there would be your exhibition. So yes, more than that, I don't know. I mean, I think there's an interesting mix really between the maybe the modern and, you know, the lamination, which was obviously seen as, you know, a fantastic technological breakthrough. The modern, and then maybe the reinvention of an older, you know, initiative. – Thanks. – And just thinking about historical models of Signals, I think, and a lot of the literature talks about they were trying to break the historical models by not having it sort of, you know, coordinated and run by a sort of London-based curatorial group, I think is what Grace Robertson said. So there's certainly a lot of literature about they're trying to break that.

But I think they were certainly influenced by Spectrum for instance. And there was a lot of discussion about that being a real sort of moment where they look to that. I haven't really looked at other historical models. And when I spoke to a lot of people, they sort of mentioned, they were kind of just making up a bit on the spot because, you know, it's so regional, it's so enormous. They suddenly realised they had to get regional coordinators involved because it was just too big. So I'm not sure they really were following anything necessarily, but that's certainly something that I wanted to delve into more in my research. – Yeah, – Thanks so much, Catlin. There's more of a comment than a question from Fiona Anderson, but maybe you'd like to respond to this.

So she says, "It's also interesting to think about amateurism in relation to practises of exhibition making as well as the taking of photographs and how this relates to the regional range of Signals and the sorts of venues being used for the exhibitions that constituted the festival outside of London." And it's interesting, I suppose, to think about, you know, although these laminated panels that were coming out through Half Moon use this kind of advertising format, I mean, that's what that lamination was developed for.

They still actually retain an awful lot of the kind of look of something, which although it's been made by professionals, it's been sort of there's like handwritten things on those as well. So thinking about amateurism not so much necessarily in terms of just the image, but also the just some of the display strategies. We are– – Yeah. Fine. – Coupling up to time. So I'll just wish… Whisk through Alex Muskogee's question. Hi, Alex, who I've not seen for years.

What do you think the… Was the impact of an imported male-dominated American art photography shown at the Photographers' Gallery, the V&A, and elsewhere in the UK since the 1970s on the appreciation of women's photographic practise? It's a big question. – That's a big one. – Well, just trying to think of it. Well, I spoke to quite a few people and they said they felt the Photographers' Gallery was relatively good at showing women's work. But I do know the V&A really wasn't. Although Mark Harworth Booth really did champion Helen Chadwick's work. It's worth saying that. And I think after… So it was really about, you know, the male art form, the great art, and that really influenced, you know, collecting works by male photographers. And even when they started to collect, speaking about the V&A, sort of gritty, documentary work, it was still male photographers. And I think by the time sort of Signals rolls around, Mark Harworth Booth really sort of started committing towards collecting more women's work and there was this awareness of really the quite exciting and experimental work that was going on by women like Helen Chadwick.

And I think it sort of started to shift a little bit and Mark Harworth Booth was really interested in getting Woolworks, which was an exhibition completely dedicated to women's photography. So I think that sort of shifted that perception and it was trying to move away from the great, you know, American documentary photographer that was sort of collected in the loads before that. That's a very quick answer because I've got to think about it a bit more, but yeah. – If I could just quickly add. So it's not entirely to do with the same subject, but I think it links to it as possibly, you know, another reason why, you know, women photographers weren't appreciated in the same way was actually that their modes of organisation were collective. And that actually they put far less emphasis on the great woman photographer and much more on, you know, collective practises. So if you look at an example like Hackney Flashers, they called… They were Hackney Flashers. They weren't the individuals involved in that collective, which has actually, you know, led to a lot of difficulties with the heritage of that work.

You know, format again. It was a woman's agency. Although there were individuals involved, you know, it was very much a collective initiative and, you know, quite rightly so as a way of supporting each other's work and practise. So that, I think that also plays into this whole history in terms of the differences between the way women and men's work was seen and appreciated.

– Thanks, Carla, and I think we'll absolutely come back to some of these questions in the round table at the end, 'cause it's also very relevant to some of the things that Laura is going to be talking about. But right now, I think we're up to time. So we're going to take a short break until 10 to 12 when we'll come back and hear papers from Theo Gordon and Laura Castagnini. Thank you. Okay. So I hope you've had a good break. Welcome back to the second part of this first session today where we've got two more papers on this theme of museums…

Of exhibitions and touring. The first paper will be from Theo Gordon. Theo is an art historian who is currently working as lecturer in contemporary art and photography at Birkbeck, University of London from 2021 to '22. He's been working as the Terra Foundation for American Art postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC, following on from his PhD at The Courtauld. And he's recently been focusing on photography and AIDS in the UK in the 1980s and 1990s. Thinking about photographers such as Dwayne Michaels and Neil Gupta in 1970s gay photography in the USA. That will be followed by a paper by Laura Castagnini who is a curator and writer whose research explores the history and current articulations of feminism, especially as it intersects with the politics of race and sexuality in modern and contemporary histories.

She was assistant curator of modern contemporary British art at Tate from 2017 to 2021 where she curated monographic displays of Lubaina Himid and Lillian Lin, as well as assisting on major exhibitions, including Frank Bowling and "All Too Human: Bacon, Freud, and a century of painting life". Very shortly, Laura will be leaving the UK to take up a really thrilling role as curator of the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, ACMI, in Melbourne, which is a sort of brilliant and… But also rather heartbreaking move from Laura. So if I can ask Theo to share his screen with us. Theo is going to be talking today about Salford and photographic history for some of the photographic history of Viewpoint Gallery that… – Can you hear me now? – [James] We can hear you– – [Clare] That's great. Thank you. – Great. Thanks very much. Okay. So thanks, James, for that introduction. And it's really a pleasure to be at this conference which has been really great the last few days.

I should just say at the outset that I come to this particular material from a very particular point of view, which is from the history of HIV/AIDS and gay and lesbian and black photography in Britain. So some of what I'm talking about is a bit of a departure for me. So it might be a little bit broad brush at times. But I'll get started. So Jane Brake had been working as the exhibitions outreach officer at Viewpoint Gallery of Photography in Salford for 10 years when the gallery closed permanently, sometime, I think, around 1999. In her recollection, the entire contents of Viewpoint's offices were skipped, including all the organisational files related to the exhibitions, commissions, and programmes that the gallery had been running since its opening in January, 1987. Brake recalled picking through the pile in the skip, trying to retrieve books and catalogues related to memorable projects, which had all been deemed irrelevant to the future of cultural life in Salford. This seems an inner suspicious end to a venue originally envisioned to become the leading gallery for viewing photography in the Northwest of England, and the second publicly-funded institution in the country devoted exclusively to the medium after the National Museum of Photography, which had opened in Bradford in 1983.

In November, 1988, according to one reporter for the Manchester's "City Life", the gallery had already become the jewel of Salford's otherwise meagre cultural offerings. Its exhibition programme keeping a balance between, quote, the accessible and the avant-garde, the local and the international. That same reporter perhaps also inadvertently noted early signs of Viewpoint's eventual fate, describing new hoardings around building sites in Salford Quays, and the desire of the city council's cultural services director to build a larger performing and visual arts centre there, which eventually opened as the Lowry 12 in April, 2000.

My connecting the demise of Viewpoint to the opening of the Lowry is, at this point, a supposition only. The small archive of newspaper clippings relating to activities out of "Viewpoint", which is collected at Salford local history library in Peel Park on Salford Crescent opposite the former site of the gallery give no indication of when and why exactly the gallery did close. In this short presentation, I want to give some sense of how the gallery developed out of the local economy and politics in 1980 Salford, and of what seems to me, its conflicting impulses in representing Salford through photography. As you'll see, I have more questions than answers. Salford City Council developed Viewpoint over the course of 1986 to open in January, '87 in the old fire station on Salford Crescent opposite the university. From its inception, the gallery was Janus-faced. Designed to house an archive of 60,000 prints of Salford's past and to commission and collect new work by professional and amateur photographers.

That sense of dual temporality was reflective of the rapid changes that Salford had undergone since the 1960s. The docks had fallen foul of the rise of the shipping container in ocean trade in the '70s. And as the new container ships were unable to navigate the Victorian Manchester Canal, they finally closed in 1982 after thousands of job losses over the previous two decades. In 1981, the government had established the Salford Trafford Enterprise Zone to encourage business investment in the area. And in 1985, in collaboration with Salford City Council who had purchased the docks in '84, they set up one of the first city action teams in Manchester and Salford. Part of Thatcher's drive to tackle what she saw as the problem of so-called inner cities. Over the subsequent years, private sector investment sought the development of new private housing and office complexes on the newly rebranded Salford Quays. Changes viewed positively by the government. So much so that a photograph of the Quays was printed on the 1988 front cover of the publication, "Action for Cities". And you can see this… That's an image of Salford there.

And so it was printed on the front cover of the '88 publication, "Action for Cities". A manifesto to expand similar programmes across de-industrialized areas in the North and West Midlands. The opening of Viewpoint in 1987 was part of the council's wider effort at regeneration. Yet the functioning of the institution as photographic archive of Salford's terraced manufacturing past, and its persistent programming of exhibitions of photography of disappeared labour, industry, and infrastructure speaks of the ambivalence, even melancholia that was accompanying the transition from docks to quays. The opening exhibition, "Hometown 100 Years of Salford", in January '87, juxtaposed archival photographs alongside more recent projects, including Daniel Meadow's and Martin Parr's 1973 collaborative project, "June Street, Salford".

Meadows and Parr had photographed families in their terraced front rooms in Ordsall, a neighbourhood previously used for location filming on "Coronation Street" in the 1960s. In 1974, the newly created city of Salford Council, which incorporated a wider of an area including Eccles, Irlam, Swinton, and Worsley began to demolish and redevelop Ordsall along with many other areas. By 1987, the street photographed by Meadows and Parr had vanished.

A later exhibition in November, 1987, similarly played with the role of photography in fantasies political character. Kevin Cummins' exhibition of large scale colour portraits called "Salfordians" provocatively opened with a portrait of Hilda Ogden before showing photographs of real community figures, local celebrities, and civic leaders inside. One reviewer, noting that a concurrent show of L.S. Lowry paintings was taking place at the City Art Gallery opposite Viewpoint wrote, quote, as you cross the street from one to the other, look up to where the sky is no longer dominated by the mills, but by monolithic tower blocks, and ask yourself whether either exhibition comes to grips with the reality of Salford in Thatcher's third term.

Perhaps one reality of Salford in the late 1980s is that photography was being mobilised by various, different parties from government to local authorities and local curators in a struggle to define the identity of the city as neoliberal economics was beginning to bite and chew upon it. Indeed during Viewpoint's development across 1986, the institution had been fiercely caught up in the contemporary Thatcherite debates over the use of local authority funding. Conservative members of the council objected to the labour majority plan that Viewpoint was not to be run as a commercial space, arguing that it would hence become a burden on rate payer's money, despite labour hopes that Viewpoint would attract some commercial sponsorship. Viewpoint's funding arrangement, 40% from Salford City Council and 60% from the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities would be the cause of the censorship of the original touring exhibition, "Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology", in summer, in 1990. A show which challenged the representation of HIV/AIDS in the UK. The council cancelled its planned showing that Viewpoint fearful of contravening Section 28 by showing work by gay and lesbian artists in a local-authority-funded space. Across the later 1980s and early 1990s, the gallery's programming centres on documentary of industrialists and remains, including a show of work by John Davis in 1987 and Ian Beasley, a Bradford-born photographer, who showed an exhibition titled, "Victorian, Manchester, and Salford" in 1988 and "Lancashire Cotton Yorkshire Wool" in 1991.

That same year in 1991, the council tried to use Viewpoint to launch an exhibition titled, "The New Era", reflecting their own rebranding at the turn of the decade. Photographer Len Grant spoke of aiming to show photographs of various areas of Salford to quote, bury the image of it being just a dirty, old town. Aiming, quote, to produce pictures so that people can look at them with pleasant surprise and say, "I didn't realise Salford was like that." In the coverage of the exhibition, It's hard to tell, though, exactly what this new era was heralding.

Again, photography at Viewpoint seems caught between melancholic and manic imperatives to envision Salford both through and without its own history. A crucial part of Viewpoint's function throughout the time it was open was the provision of dark room facilities and community engagement programmes, encouraging local people in Salford to produce their own photographic images. Whilst its funding model was singular, complex, and contested as we've seen, Viewpoint's community dark room firmly placed the gallery in the wider context of photo galleries in the North that were creating audiences and extending their reach into local communities by enabling people to gain experience with photographic production.

These venues included Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool and Side Gallery and Spectro Arts Workshop in Newcastle among many others. This included frequent work with children as seen here and on encouraging amateur women photographers here to produce work, to participate in an open exhibition at the gallery in Liverpool in '94 as part of the Signals festival that Catlin was discussing earlier. The reach of Viewpoint into the community also drew on the legacy of Salford-80, the pioneering photo festival across multiple venues in Manchester and Salford in 1980. Neil Wilkie, keeper of photography at Viewpoint, had worked on Salford-80 with the local artist and spearhead, Harold Riley. And the festival had been massive in scale. And I'm just showing you one of the back pages of the special issue of "Creative Camera", where they give some sort of compendium of highlights of things on display at Salford-80.

The festival had been massive in scale. Described in a special devoted issue of "Creative Camera" as marking, quote, a new departure in the scale and the presentation of photography exhibitions in the UK. Salford-80 intertwined exhibitions of internationally renowned photographers, including Charles Harbert, Russell Lee, and Andre Cortez with work addressing the locality, introducing a step change in appreciation of the integration of photography in daily life and imagining self and history. Viewpoint attempted to take up this model, especially through community dug from work. Whilst in its connections to other photography institutions, it was able to participate in the launching of several innovative exhibition projects, notably, "Fabled Territories: New Asian Photography in Britain" in 1989 with Leeds City Art Gallery. The junking of Viewpoint's archive makes it difficult to appreciate the complex role a gallery like this played in the changing status of photography, both in gallery spaces and throughout wider community cultures across the '90s.

I want to end by looking at one project that the photographer Chris Harrison exhibited at Viewpoint in 1994 that demonstrates the clear potential of the gallery to commission important work, cutting against its own frequently historic understanding of labour and social inequity. Harrison had completed his studies at Trent Polytechnic in 1990, and since completed the work titled, "Whatever Happened to Audra Patterson?" Addressing the fantasy afterlife of a class photograph from his school days in his hometown of Jarrow on Tyneside.

In 1993, Viewpoint commissioned Harrison to produce work based in the Salford neighbourhood of Pendleton, an area of high unemployment, where he first spent time establishing contact with local community organisations and groups, including State of Independence, a video cooperative resident on the estate who introduced him to some of the local men. Harrison set up studios at the Phoenix Project Theatre and Stars Community Centre in Pendleton and invited men to sit for portraits dramatically front-lit against burgundy velvet drapes. State of Independence taped Harrison and the men interacting. And both the portraits and video were exhibited at Viewpoint in 1994 in an exhibition titled "Under the Hood". As maybe apparent, the photographs draw on the iconography of 16th and 17th century portraiture on the Italian peninsula as well as English society portraits by Anglas McBain and Cecile Beaton inviting close appreciation of the careful sartorial choices of the men and their mode of presentation through the camera.

By 1993, the mass unemployment of the early Thatcher years had been set in for a generation with many residents of Salford seeing no benefit from the private regeneration of the quays. Rioting had broken out across the city in the summer of 1992. Val Williams has been a great champion of Harrison's work and wrote well on the relationship between photographer and subjects in "Under the Hood" in a "Guardian" feature on the 18th of June, 1994.

I'll just quote a little bit of Williams here. "Chris Harrison's photographs are uneasy statements. Implementations of both violence and grandeur and express an intense curiosity, showing an exchange of gazes, which are both wary and narcissistic. But Harrison's photographs are redemptive too. They insist on reclaiming status for those judged by society to be worthy of none. If the men in these photographs emerge with a kind of holiness, then perhaps this is simply an acknowledgement that the line between saints and sinners is a fine one, and that both are possessed by a peculiar madness." I don't have time to embark on my own analysis of the work here.

But we'll underline both the prevalent homoeroticism in the work and also that Harrison's work was only one of several commissions by Viewpoint in the early '90s of photo projects that had to have something directly to do with the communities in Salford. And study of which would make fascinating contribution to understanding of the multiple ways that people here were being produced by and through photography at this moment. Even if all this work had been consigned to the skip by the council. And that's the end. Thanks very much. – [James] Thanks so much, Theo. So we'll have questions after both papers are done. So do pop some questions into the Q&A so we can be ready for that. And Laura, are you ready to share your screen? Yeah. – Sure am. – [James] Great. – Or am I? Sorry, one sec. Can you see that and can you hear me? – [Clare] That's great, Laura.